Billie Jean, Me, Barbara Streisand, and How to Start a Movie Career with Your Neck Ripped-Out!

Long ago, my thesis advisor, a charming professor named Arlen Hansen at the University of the Pacific, coined the term Contsellationizing for the phenomenon of Pareidolia—the universal tendency in human perception to generate new patterns, such as animal shapes or scary images, out of other images. When you stretch out on a blanket with friends, staring up at a blue sky rich with cumulus clouds scudding by, and a mock argument breaks out, ‘I see an alligator, right there! No, no, I see Thanos rising up! Wrong! I see a ‘bloat of hippos’ and, look, they’re trampling a hunter with a rifle!’ — you’re Constellationizing. The Greeks, of course, did it with stars; Rorschach tests rely on it, and as for the paintings on Neanderthal cave walls, Arlen said he thought some of the drawings were cave artists, Constellating dark mineral and water stains on the rock. But here’s the thing: when you do it, just remember you didn’t make the clouds! Or the stars! Or the cave walls. You’re just riffing on something inspirational that was already there! Now hold onto that idea while I start this story.

*********

Once upon a time, it was almost impossible for a moviegoer to see a screenplay. In fact, many people didn’t even understand a film started with a screenplay. As much as I loved movies growing up in Philadelphia, moviemaking was as strangely mystical as other religious rituals. Even if, somehow, you found out movies began with a script, except in L.A. and maybe New York, no one you knew had one. Most likely, even I found one, I wouldn’t know how to read it. By the time I entered college in the 1960’s films were starting to be rigorously studied in colleges, but in the majority of schools, cinema was approached the same way novels were studied: in English departments, where we would discuss themes, contextualize plots and ideas, form essentially literary character studies. Of course, a magnificent tracking shot or jolting edit of an action sequence would be noted. Still, unlike today, no one expected it was possible to become part of that world. Movies were made by, well, those people. Out there. On that coast. In the welcoming darkness of our plush, stately, single-screen movie theater, The Renel, with its faux balcony and Rococo details, movies always felt like a dream to me. But being part of that world was…un-dreamable. Of course, today a couple thousand schools assure young students, as they take their tuition, that you too can have a career in film and TV by taking their courses! (Even though in most cases the courses are taught by professors who themselves never even tried to have a career in the marketplace.)

This is a story about how I broke into the movie business. But it’s really about a brawl I never had. Follow along. It starts back in spring of 1978, when all of a sudden, I had to become a grown-up.

I had let graduate school in English literature be my welfare system. A strange and distant place, like a tropical island, with its own weird flora and fauna to hide away from the real world. I was always able to finagle a Teaching Assistantship/Fellowship and so never had to pay tuition. I also earned a tiny stipend, which let me live a degraded bachelor’s life. At last, in 1978, after I’d earned a Doctorate, I was ‘getting kicked off the island.’ All my friends and colleagues were madly applying for college teaching jobs. But I knew I was kind of a scam as a scholar. Grad school was fun because I loved my specialty, Middle English, which had an unacknowledged Lord of the Rings aspect to it, a discipline with myths and devils and faeries. I was not, however, the slightest bit interested in the academic grind, the departmental competition, the pretensions and infuriating jargon of the requisite critical articles and books. One quote that best describes academia to me is this: ‘The reason academics are always so angry is because the stakes are so small.’ While I knew I did not want to be a college professor, I was too timid and, frankly, ignorant, to consider doing what I really wished to do: find a way to make movies. A far more consequential and earth-shattering event informed my ultimate decision.

On August 11, 1976, my older brother, Harold Wallace Rosenthal, was on a tour of American embassies along the Mediterranean for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Harold had been Chief of Staff for Sen. Walter Mondale and was probably going to follow him later that year to Jimmy Carter’s White House. Now he was the Senior Adviser to NY Sen. Jacob Javits, who chaired the committee. Harold was finishing up his penultimate stop in Istanbul, Turkey, when he was killed by PLO terrorists as he stood in line to board an El Al plane to Israel. Security had blocked several terrorists from breaking onto the tarmac and hijacking the plane, but the terrorists fired off shots and then threw a hand grenade. My brother Harold was, as far back as I can remember, late for everything, and on this day, the last four people in line were killed. This is a story for another time and place, but its consequences have never ended for my family and me. In the nightmarish days waiting for his body to be flown back from Turkey, I made a vow to myself that I had to learn a lesson from Harold’s death. I had to! In the end, I decided on two inescapable lessons to guide me for the rest of my life. First, life is frail and requires great good luck, so being too timid to try and achieve a goal, even a very difficult one, can be ruinous. Second, a sacrament I borrowed from St. Loyola’s Spiritual Exercises, one of the books I’d only have read in grad school, which is why I stayed there, is the imperative to use your imagination to feel the suffering of others. And given what’s going on in the world today, I use it more than ever. When I read a newspaper article, whether it’s about a plane crash in India or a drone attack in Ukraine, and they list ‘numbers killed’, I make myself stop and meditate on the fact that each one of those ‘numbers’ represents a family like mine. So, after I finished school at the University of the Pacific, in Stockton, CA, my doctoral adviser, Arlen Hansen, and some friends celebrated with me at a late dinner — topped off with some then-illegal smoky inspiration. By about 2 A.M., I finally jammed everything I owned into a 1968, two-toned, 8-cylinder Olds Cutlass, which was my brother Harold’s car when he was killed. I packed a lot of LPs, a component record player, a few clothes, and, leaving around midnight, drove the length of California on Interstate 5. to L.A. With a couple of stops to sleep in the car, I found myself by morning on the massive vehicular whirlpool of rush-hour traffic on the Sepulveda Pass. This is a hill that leads from the San Fernando Valley down into Los Angeles proper. It felt like a hundred lanes of cars. (Still does.) When traffic came to a stop, I realized the chaparral on both sides of the 405 was on fire. Dark smoke lazily drifted across the freeway. My car was boxed in, and there was no way to exit. I didn’t know what to do. I assumed I had to do something! I turned to my left to check the car beside me, and I saw a very pretty young woman leaning close to her rearview mirror so she could put on her mascara. She wasn’t paying attention to the hill fire. Looking around, I realized…no one was. Now this was at a time when you drove across country, cars didn’t have cassette players or CD players, and certainly not Satellite radio. You would lock onto an AM station for a while until you drove out of range. The farther into the Midwest or deeper into the South you drove, the more the stations turned religious or country. But every once in a while, you’d be proximate to a college radio station or some small-town hipster station and, miracle of miracles, you’d delight in 30 minutes of cooly-curated, surprising, inspiring music. It made you feel like an Explorer. ‘I found this incredible progressive station in Nebraska! The music it’s playing moves me and I feel like I’ve uncovered a hidden paradise, and no one knows about it, but I want to live there!’ In the middle of this freeway traffic jam, with the hills burning, I felt I had just been clued in to a very cool secret. L.A. is a song about a whole new world.

I had no contacts in show business. Zilch. Nada. Actually, in 1978, I had no ‘contact’ in its denotation of ‘a state of physical touch’. I couldn’t feel what making movies was like. If you want to be a lawyer, you can imagine how you have to speak and dress and carry yourself, and you’ve heard about law books and court cases and, well, everything. When I came to L.A., the protocol, terminology, deportment, appraisal, all the ways you understand what you need in any line of work, was not accessible to ‘civilians’ like me, except in dramatically excessive films like SUNSET BOULEVARD. Then I had my first dose of good luck. After struggling to find a place to live, I ended up in Silver Lake, then an old ‘starter neighborhood’ in L.A. The reservoir still had water in it. The hills had glorious old homes and bungalows from Raymond Chandler’s California. I jogged those hills every morning and circled the Lake just to expel anxiety and self-doubt. (I was fanboy thrilled that I finally understood the title of Jackson Browne’s haunting song ‘From Silver Lake’!) A new friend who was a Script Supervisor, on her way to becoming a director, told me I could make a bit of money by reading scripts for studios, directors, and producers. But it’s a hard gig to find. ‘Readers’, as they’re called, waded through stacks of script submissions. There were also ‘Story Departments’ at the studios that hired Readers. ‘Look in Variety!‘ So, I went to a huge newsstand in Hollywood, a cool hangout in those days, packed with wanna-be’s like me staring at rows of bright magazine covers, hoping one of them held the secret to a fabulous life! I perused an issue of Variety (far more jargony fun in those days!) and spotted a feature on a brand-new studio, ORION PICTURES, formed by three executives at United Artists, now just ramping up. Next, I did something innocently idiotic in retrospect. I simply called the studio’s Story Department. No, I didn’t have a name, an approach, a reference, a track record, or a clue what a Reader was actually supposed to do. My actual lucky moment came because I called at lunchtime. (When you’re out of work and with zero options, the day’s structure tends to dissolve.) But instead of getting a receptionist/secretary who surely would’ve told me to go far, far away, the office was closed, the phone was answered by the delightful and sardonic Sara Altshul, Head of the Story Department. I stammered about wanting to be a Reader and, lucky again, instead of inquiring about my experience, she said, ‘Well, it’s funny. I just fired one. If you can get here in half an hour, I’ll give you some scripts. Come to the Warner’s lot.’

I literally did not know where WARNER BROS. was. (ORION was on their lot.) I wasn’t even sure where ‘The Valley’ was! I unfolded a Texaco Road Map of L.A. and found Barham Road. It was hot in the valley. Inferno hot. Running out of time and confused by all the Gates, I parked my car illegally — next bit of luck? no ticket!– and ran to the first Gate I came to. I told the Guard I was expected at ORION. Lucky yet again, he just waved me through. Sara hardly looked up from the piles of screenplays (all hard copies in those days) on her desk. She handed me a stack of scripts to read overnight. ‘Bring me coverage tomorrow.’ She never noticed me drenched in sweat, eyes wide, afraid to ask, ‘What’s coverage?’

As a rookie, still infected by academia, I stayed up all night and wrote literary essays about each script. All that was missing was a final Bluebook. I even used Latin critical phrases to delineate the themes and plot of each script as if they were part of a renowned short story collection! I proudly brought them back the next day. …What happened next was more than luck. Sara read through my ‘coverage’ in front of me. Anyone would’ve kicked me out while admonishing, ‘You have no clue about this business. Go teach at a Community College.’ Instead, Sara was gently scolding, ‘Look, I just wanna know if a script could generate some box office?’ Lucky-lucky again. Sara took pity on me, and with the clarity of a Hollywood epiphany, I got what she wanted. Soon, I became an in-house Reader for ORION.

As I read and read and read screenplays, I began to evaluate not only the commercial viability of each script but also take apart the style and the look of each script. By ‘look’ I mean — you can treat a script not just as a blueprint for a movie, but also as a work in and of itself. I began to set aside scripts that I thought were written by creative stylists, writers who were introducing new techniques. The ‘flow’ of a screenplay is crucial to getting an executive or director to stay with it. Tony Gilroy, Shane Black, and David Koepp are all innovative stylists. Soon, I had strong opinions on how to write a screenplay. One e.g., I noticed some writers were dropping many of the production conventions of a script (things like camera angles, slug lines, CUT TO or full scene locations, INT./EXT.) It often made the script read faster. Someone like Shane Black revolutionized script writing by even addressing the reader! (To paraphrase, ‘Hey, I’m about to write a sex scene here, but if you’re like me, you find them silly to read, though fun to watch. So let me just say I hope my mother doesn’t read this part!‘) Sure, I was deciding on a style, but I was still afraid to write something of my own.

I continued as a Reader for the immensely charming director Mark Rydell while he was shooting THE ROSE (one of the most brilliant ‘rock and roll’ films ever made that is today sadly neglected; Bette Midler deserved an Oscar!) and later directing the saccharine ON GOLDEN POND. Reading scripts provided enough money to live in a teeny studio apartment and eat burritos — and I lived near Yucca’s Food Stand in Los Feliz, the exquisite paragon of burrito-ismo — but I was also feeling lost. Every morning I’d jog from the flats into Griffith park, past the Greek Theater, up to the Observatory, and then onto the trail that leads past ‘Dante’s View’, a tended grove in the hillside, and then out along the apex ridge trail which afforded views of The Valley and the city, back then a vision painted in brown and viscous smog, where I saw my first rattlesnake sunning his bright tummy. (I’m still enthralled by the evolutionary defense system of these essential critters.) When I came to L.A., newspapers were still only physical things. One day, I was sitting on the stoop of my small apartment building of studio-sized apartments when I saw a short article in the back of the International Section of The New York Times about a young woman named Phoolan Devi, later known in India as the ‘Bandit Queen’. She was a teenager who grew up in poverty in a village in Uttar Pradesh. She was assaulted by men of a higher caste but knew the police would not care less what happened to someone like her. So, she gathered her young friends and formed a gang of dacoits (bandits). Her gang attacked the village of her higher caste abusers and burned down their homes. Everyone thought she would turn herself in and beg for mercy, but instead, she defiantly went on the run. Here’s the thing: the police couldn’t find her because as the story spread, her many sympathizers began to hide her. The hunt reached across India, but she always outmaneuvered the police. In the end, she only agreed to turn herself in if the police chief would kneel to her in public and apologize for how she was treated. I thought, ‘I think this is a movie.’ Screenwriters often talk of ‘seeing the movie‘ even though our medium is words. I always imagine that while a writer is the only one on a project, whether by spec or assignment, the writer encompasses an entire film crew, executive building, marketing division, front gate guard, and acting coach inside their head. (Pronoun-scolding safe; not a solecism; yes, agreement would take the singular!) I knew this would be the plot of my first script.

In 1983, a new city shopping center called The Beverly Center had just opened. People were appropriately outraged that a suburban shopping center was built to loom over the cute shops and restaurants near Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Beverly Hills, but for me, it was gleaming and new and free to enter. I was feeling entombed in my tiny studio apartment and decided the food court at The Beverly Center would be my office. It had new bathrooms and payphones, food, obviously, and afforded floors like delightful boulevards to saunter while brainstorming, daydreaming, avoiding work, window-shopping, plus a California Mardi Gras of beautiful-people-watching. I started to noodle the scenes on a yellow legal pad, but then my soon-to-be writing partner, Lawrence Konner, who was doing television with a company called 10-Four, let me use a proper office. The script seemed to write itself. In fact, it only took about three weeks. I could see every scene and every character and hear the dialogue. I called it LEGEND, just to be a little tongue-in-cheek, well, very tongue-in-cheek. I set the story in Florida with trailer park kids and, in some ways, anticipated Trump because in hot and humid Florida, I made the antagonist a very MAGA-type store owner. I tried hard to dramatize the caste system that exists in the United States and satirize the dangerous middle-class of white small businessmen who live with their grievances like family. The ones who today think rich hustlers like Donald Trump are ‘their crowd’.

I gave the finished script to a friend who worked as an assistant to Mike Simpson, a major agent at the then William Morris Agency. He gave her back a list of ‘notes’ (my first encounter with these insidious lists of changes from people who are not artists; in no other art form do the business-moneymen feel so completely comfortable telling creative people how to make art ). My TV friend, Lawrence Konner, on the other hand, gave me some new solid ideas, and we went through the script again. He also knew an up-and-coming agent named Bill Block. We agreed to work together, and he sent the script off.

At the very same time, back in my hometown of Philadelphia, my father, Sid, had his third heart attack at 70 years old. All the men in his family had died young of heart attacks. He was rushed into a triple-bypass at a time when stents were not used as frequently as they are now, and the procedure meant cracking open his chest. I flew back and, in the ICU of Jefferson Hospital, after my father survived the surgery, I used the old phone booth outside the ICU to call L.A. and see what was happening with the script. It turned out the script sold within days to Tri-Star with Jon Peters and Peter Guber producing, successful men who would soon take over SONY. My first script. My first sale. It seemed…well, hallucinatory to me. I didn’t know enough to even think about who would be involved now before we sold it. Later, I learned there was interest from many studios, but my partner‘s agent wanted us to go with Guber-Peters.

I stayed in Philly another two weeks till my father was home and settled, and flew back. I was excited, but again, I had zero clue of what would happen next. Nonetheless, as the plane descended into LAX, I imagined hanging out on set, kibbitzing with the actors and crew, and maybe even stealing a cameo!

The phone was ringing in my teeny Los Feliz studio apartment as I fumbled with keys to get in. It was a two-story building of all studios (still there!) on Ambrose St. Rushing to grab the phone, I was already thinking I’d soon find a bigger apartment. Maybe even a grown-up’s 1-bedroom! ‘Hi, it’s Matthew Robbins, and I’m going to direct Legend!’ Matthew Robbins went to college with a group that included Spielberg and Lucas, and had written the poignant Sugarland Express and was also a 2nd Unit director on Close Encounters of the Third Kind. To me, this placed him in rare company. The producers, Jon Peters and Peter Guber, partners who would soon take over SONY, had already hired him. I made a mental note — ‘I guess my opinion in these matters doesn’t isn’t required!’ Nonetheless, I assumed the director was calling to set up a meeting to give me his notes and start the next draft. This is contractually obligated by the WGA, West. Instead, he said, ‘Hey, Mark, look, I’m a writer, too, and it’s hard for me to direct something I haven’t written. I like your script, but I’m going to rewrite it.‘ He explained that he had directed a film, Corvette Summer, that didn’t do well at the box office, and he felt one of the many reasons was it started too slow. It is true that to emphasize the class dynamics swirling around Billie Jean, we opened with Billie Jean being driven by her brother to apply for a job, but then rejecting the offer when she realized she’d be taking the position from a poor woman fighting to get a court to let her have her children back. Director/actor Keith Gordon, who played ‘Lloyd’, recently commented in IndieWire ‘that the whole thing (our script) was about a scooter’. Besides the fact that he never saw our script because the script was rewritten by Matthew Robbins before casting. By the way, saying our story was about a scooter is as simple-minded as saying Wizard of Oz is ‘about’ red shoes. The scooter functions as a synecdoche — look it up, Keith! — standing in for how precious a luxury is to people who aren’t affluent. (I have to mention also that the journalist, Mike Ryan, in that IndieWire anniversary piece dumbfoundingly makes it seem I stalked him (…’for the life of me, I don’t know how he got my number’) when in fact my agent forwarded me Ryan’s query email requesting to speak to me!) Matthew got off shortly after a few clipped sayonaras. That was my last connection to my script — a bewildering betrayal I learned later was simply the way things were done by most directors. A script that gets a ‘green light’ is like the smell of hot blood and living flesh to the zombie legions that make movies. It drives people mad. ‘Did you hear about that picture? It’s going into production! I need to get on that picture! I am on that picture….It is my picture!’

A few months later, Lawrence and I actually wandered by the production office uninvited to meet Matthew Robbins and his writing partner for this project, Walter Bernstein, a legendary screenwriter who’d been Blacklisted in the 1950’s and who wrote a wonderful movie about it called THE FRONT, where most of the actors and crew themselves had been Blacklisted. But union-schmoonuion, fired writers were not supposed to be visible. Matthew and Walter were so stunned when we peeked into the office that after a few pleasantries, everyone fell silent. As in, ‘Would you please get the fuck out of here?’ We watched them printing out their new version. Of our script. We made some awkward jokes with the Producer, Rob Cohen, who was very friendly and compassionate, and then left quickly feeling humiliated. Yet, the truth is we should’ve been allowed at least to do the one rewrite. Walter Bernstein was a good writer and a good man, but he had no feel for this story, and I guess, progressive or not, when it comes to writers replacing writers, which is where many writing jobs come from, writers forget union solidarity. We in the WGA never call ourselves ‘scabs’, but in a way, that’s a big part of how we find jobs.

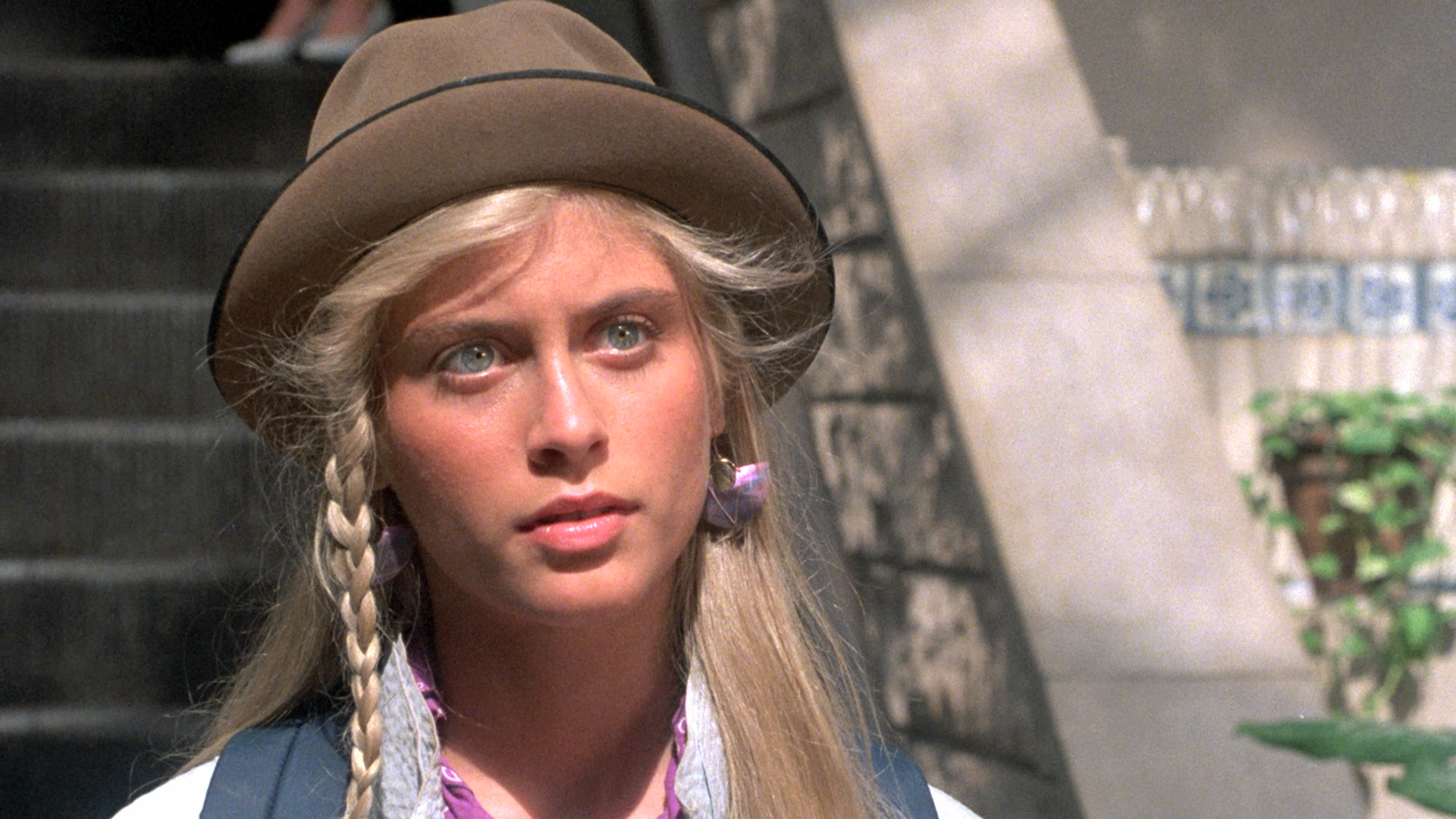

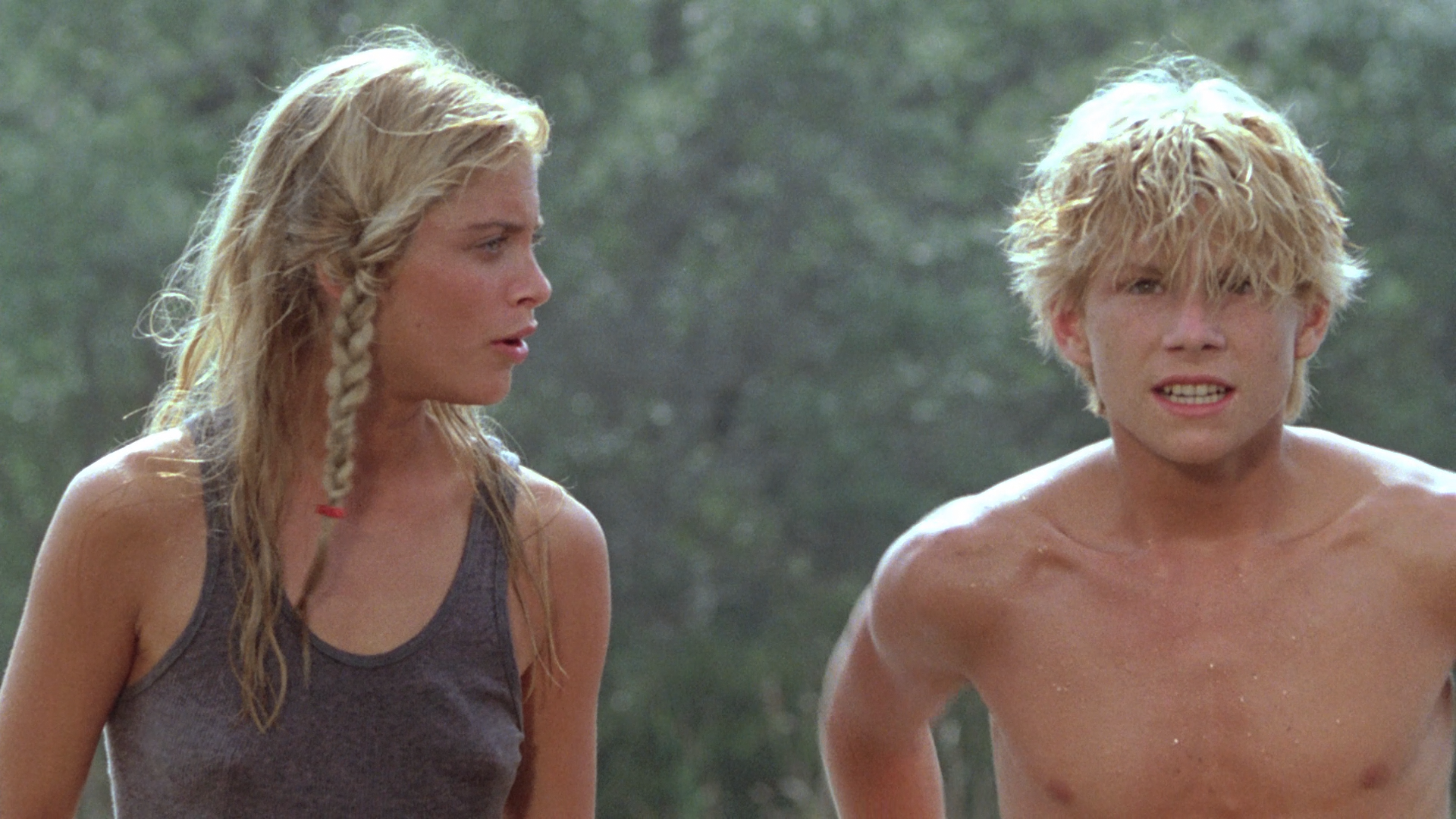

The sober truth is, we are the sole credited writers on the script because most people wouldn’t notice the changes made by Matthew and Walter, other than moving it from Florida to Texas. Texas makes the violence a cliché; it’s what we assume about Texas. I’d like to take credit for seeing that sleepy Florida would eventually turn into a raging MAGA machine. But if you look closely at the film, what Matthew and Walter actually did was to soften its working-class themes and file down its rougher edges. Jon Peters, the producer, as Donald Trump might say, was not ‘the sharpest light bulb‘. I think he decided it could play like one long music video. It meant losing scenes where we got to know the working-class young women hiding Billie Jean and, instead, we got pretty young people lighting candles as if they were at Woodstock. The story was the same. It’s just that the tone was off. ‘Tone’ in a film is created by an accumulation of tiny details, maybe a day-player performance, or a location choice, or a few changes in dialogue. Still, they had a wonderful cast, yes, including Keith Gordon. It was one of Christian Slater‘s first movies, plus it showcased the incandescent Helen Slater, charming Yeardley Smith, and Peter Coyote. It also had a heavy Pat Benatar soundtrack. (Later, we heard some rumors that Jon Peters skimmed a lot of money from the soundtrack budget, but that’s something I can’t prove) Then again, no one who made the movie knew the origins of ‘Billie Jean’ — it was certainly notthe Michael Jackson song — nor did they know that the Christian Slater character, Binx, was based on the lead character in the award-winning Walter Percy novel THE MOVIEGOER, a young man who is trying to find a more authentic way to live.

During a rainstorm in L.A., when I was in Westwood, the part of the city that serves UCLA, I saw people handing out tickets to a rough-cut screening. A way to get an audience’s reaction before a film is ‘locked’. I was stunned to realize it was for THE LEGEND OF BILLIE JEAN! (Our original title, LEGEND, had to be changed because Tom Cruise had a new movie coming out with the same title.) At first, they wouldn’t give me screening passes since they wanted mostly young women, but these are moments when, as my kids call it, ‘My Philly’ comes out. ‘Yo! Two tickets, putz, now!’ A few weeks later, we stood in a long line outside an MGM screening room in a light drizzle with a bunch of young girls, the target audience. Later, as the rough cut played, I couldn’t help but focus on all the spots where they made wrong choices. I fantasized printing out copies of my original script and handing it out at movie theaters across America!

Sorry, it’s taken a while, but here comes the point of this story! Okay, maybe I’m disingenuous, but the story of how I stumbled into a screenwriting career is teleological — heading intentionally to what happened next:

THE LEGEND OF BILLIE JEAN finally came out. It was not well received. It bombed at the box office. Even though it was later going to become a ‘cult’ hit over decades — just recently a friend of mine saw a young kid wearing a Billie Jean Fair is Fair! T-shirt on the New York subway — the original release was a painful lesson of ‘Be careful what you wish for!’ Want a movie with your name on it? Then your name will suffer the ridicule. In a strange bit of karma, we had been working in Morocco that year on the set of THE JEWEL OF THE NILE, doing rewrites. I received an international call at the hotel, not a common thing back then, from the director Matthew Robbins. He had obviously been denied credit by the WGA, West credits committee. He asked me if I would tell the Guild to put his and Walter Bernstein’s names on the picture anyway. If you check the WGA Credits Manual, a new writer has to do substantial work to get credit on an original script. Usually. There is no credit due for simply ‘dumbing down’ a screenplay. Okay, okay, here’s the climax!

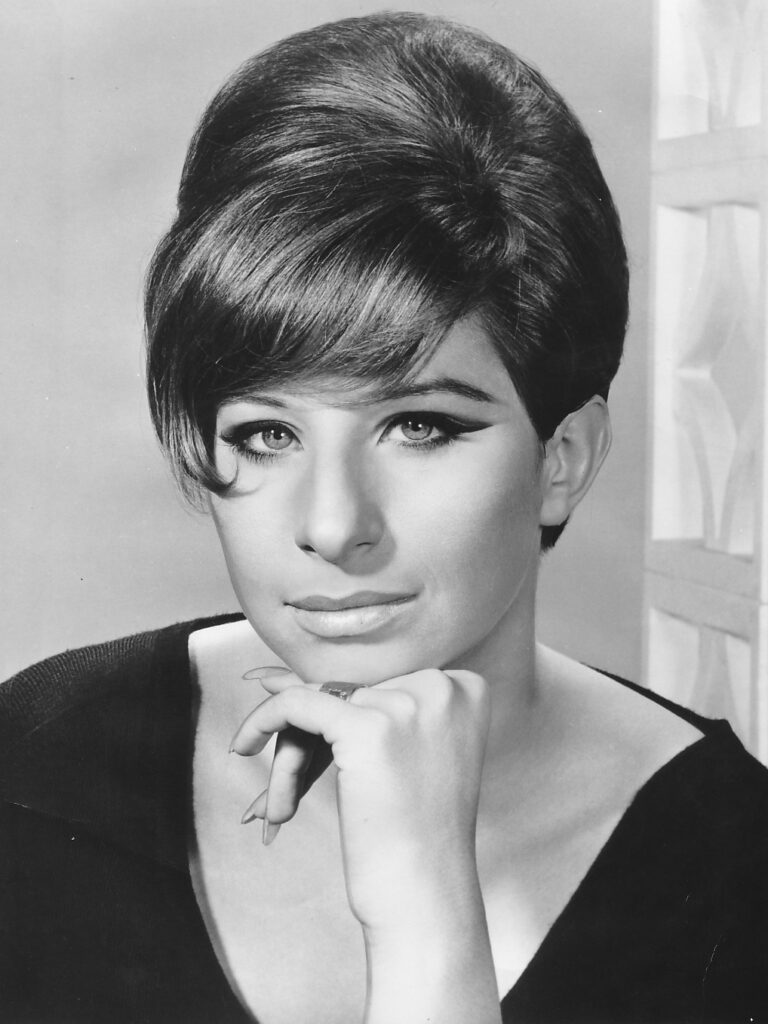

When BILLIE JEAN bombed on the weekend, the following Monday I impulsively typed a sarcastic letter to the producer, Jon Peters, telling him that maybe the film would’ve played better if he didn’t kick us off our own script. Well, maybe the letter was in truth a bit more contemptuous, mocking, jeering, and taunting. This was before email, so I had a messenger hurry it over to Jon Peters’ office. A few hours later, I was stretched out on a sofa in an office at Universal working on our SUPERMAN IV script. My partner Lawrence Konner was at the desk, tilted way back on the desk chair. Here’s what happened next: The phone rings, and he casually answers. Suddenly, he slams the phone down and pops up straight. ‘It’s Jon Peters and he sounds really, really angry!’ Enter Philly! The phone rings again, and my partner won’t answer. I quickly grab the phone. Jon Peters begins screaming, ‘I am going to rip your throat out. You are never gonna work in this town again. How dare you send me a letter like this! I will beat you senseless! You’re done! Don’t you know who I am?’…And before I tell you the next thing, he said, and I will swear on the Bible, he said it — well, I’m an atheist, so on anything else — plus I will swear on my children that this is true. What he says to me next says a lot about this hugely successful producer, who runs Hollywood, and also, as I thought back then, says a lot about who Jon Peters was living with at the time. ‘I’m a big shot. I fuck Barbra Streisand!’

I just remember wondering two things: what kind of person (Barbara) would live with this guy, and second, why would he ever say that to me? I was a nobody. A young guy with one film and freshly starting out. Why try to impress me? My anxious partner watched wide-eyed as an uncontrollable ‘Philly‘ reaction began, ‘Sure, Jon, sure. You’re gonna rip my throat out? Sure, sure, sure…‘ And the louder and longer he went on, the more I simply taunted him, ‘Sure, sure, sure, sure… ‘ But when he started to howl, ‘I know guys. I’m from the street!’ I taunted him, ‘You’re not from the street, Jon. You haven’t even touched the street for years! You ride in the back of limousines! Do you want to meet me somewhere right now? I’ll come over to your lot. Or you can come over here. I’ll meet you on Burbank Boulevard if you want!’ Now, Jon Peters was notorious for his weight-lifting obsession. He was pumped and broadly muscular. He certainly would’ve pummeled me into a heap. But as we know about bullies, Jon was so caught off guard by my teasing him and chanting let’s do it let’s do it let’s do it let’s do it that by the end of the call he kind of grumbled and then said, ‘All right, all right, I guess I deserve a punch in the jaw. Maybe we should’ve kept you on.‘ And then he hung up.

No writer ever gets used to being fired from a film, particularly when it’s an original story. And, yes, if you can sustain a career, you will be fired at some point. I think most of us remember the times we’re fired even more than the thrill of selling a script or being hired for a solid assignment. So, how to contextualize this process of directors (and producers & executives) transmogrifying original scripts? Remember what I said about Constellationizing? If a script works well enough to be sold and attract filmmakers, it’s also valid enough to trigger that process. Maybe call it an act of Fan Fiction? Mental riffing on a story that’s hooked you. No, I’m not saying that re-writes, rehearsal, and above all casting (‘Hey, let’s lose Orion and put in Odysseus, he’s a much better actor!) aren’t crucial. But the writer is the only one who works ex nihilo — out of nothing. There is a great Dire Straits song called ‘Making Movies’ about a young girl roller-skating through the streets with a headset on while the song she’s listening to makes her feel like she’s in a movie. I’ve never had an actor ask me about the character they’re playing. And to be fair, film is a director’s medium. Plus, there are screenplays that present little but a vague idea for a film that must be Constellationized. TOOTSIE is a great example of the power of rewrites. The story spread around Hollywood for years was that it started out as a roman a clef movie about the notorious Billie Jean King v. Bobby Riggs tennis match, then winding its way through a dozen writers before it ended-up being about an actor who becomes a better man after he has to dress a woman to book a job and sees what women actors must endure. This was not the case in LEGEND OF BILLIE JEAN. It was not a Marvel movie done almost in pieces, set piece by set piece, where the studio has almost shot-by-shot control over the process.

THE LEGEND OF BILLIE JEAN was my baptism of fire into the movie business. The Time Loop that connected a not-very-scholarly academic dropout with no job or savings sitting alone in a shopping center thinking about an Indian bandit girl and my screaming match with Jon Peters was merely the first of many Time Loops that to me form a writer’s experience making a film. Writers start a project as an incorporeal act of the imagination, alone with their thoughts, and far away from the very bone and blood of businesspeople who intrude later. ‘Fair is Fair!’ was the tagline I gave Billie Jean. I used to say that as a boy in Philadelphia. Billie Jean — and, yes, the magical Helen Slater– deserve their spot in the stars. But writers put the stars in the sky.