“Most people are nostalgic for things that never happened.” — John Updike.

Remember the seagulls in Finding Nemo? They had one word of dialogue. Relentlessly shouting ‘Mine! Mine! Mine!‘ whenever they see food. The simplicity of their reaction evokes children who commonly use “Mine!” to assert possession. I guess this is the metaphor I’m pushing here: screenwriters often do the same thing. In Hollywood, it’s common for several writers to work on the same project in various capacities. Some have done the original work; others move in for a couple of weeks to adjust scenes for the director. But once a movie project is given ‘the green light‘ (meaning it has been slotted for production), many writers who are ‘short-timers’ are like gulls swooping down to steal a half-eaten sandwich from other gulls. ‘I wrote it, too! is their version of ‘Mine!’ End of metaphor. The Writers Guild of America (WGA) credit system, meant to ensure fair attribution for creative work, can quickly become a wacky battleground where screenwriters, often scrappy and desperate, will do anything to get their names associated with a project—even if their contributions amounted to little more than a couple lines, a scene or two, or nothing that was included at all! Every writer who ever did a draft of a script feels the pull of glory, ‘I wrote a scene! No, er, I meant I wrote the important scene! Wait, no, I wrote that film! I should get a credit!’

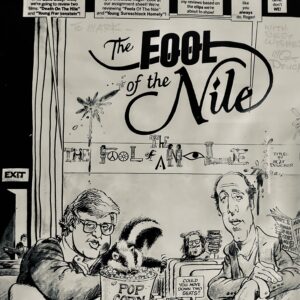

When there is more than one writer on a film, the WGA credit system depends on a committee of writers who look over all the material, all the drafts and previous materials, and then assigns credit. Back in the 1930’s when the writers’ union first formed, the studios held on to copyright (huge mistake by us!) but eagerly gave away power over credit. They knew they’d be sued if a writer objected. Most writers are loathe to sue the union that tracks their residuals. While I have been involved in many arbitrations — and have lost some — one arbitration that was easily decided was the writing I did with my partner Lawrence Konner on The Jewel of the Nile. The 1985 sequel to Romancing the Stone. And while I have many amusing stories about that epic action-adventure project and had a wonderful time with the producer and star Michael Douglas, I have also had a couple of seagulls, er, I mean writers who worked very briefly on the script hovering above. They were TV sitcom writers, Ken Levine and David Isaacs, brought on for a quick pass and while they were denied credit by the WGA, now almost 40 years later they resurface to continue trying to snatch a hunk from us.

But the story also involves orangutans. So be patient!

In 1983 we had just sold our first script (it came out as The Legend of Billie Jean and we were fired off it by the director the instant it sold, but that’s another saga). We were told that Michael Douglas liked our original script and was looking for someone to write the sequel to Romancing the Stone. Writers were coming in and pitching Michael all kinds of ‘treasures’ because of the ‘MacGuffin’ in the first film — look it up! — was an immense emerald found in Colombia, South America. It was also clear a new locale for the sequel would make sense. Part of my family is from South Africa and my dream had been to see the Serengeti because of my deep love of wildlife. And then an idea hit me. I had done a paper as an undergraduate about the Nile River and its legends. One of those stories was about El Mahdi! Part of Shia, Sunni and Sufi mythology. Savior, magical, supernatural marvel, one of his honorifics was ‘The Jewel of the Nile’! Now I can assure you neither Isaacs nor Levine know this origin story — but on we go.

As soon as we told Michael, ‘What if the MacGuffin is a jewel — but not a stone. A person!’ he hired us. That summer we worked on developing the first draft with both Michael and Robert Court, the Fox executive on the project. The next thing we knew, the rest of the cast — Danny DeVito and Kathleen Turner — agreed to return, a director, Lewis Teague was hired, and we waited for production rewrites to start. It was August.

By November we had still not received any rewrite notes.

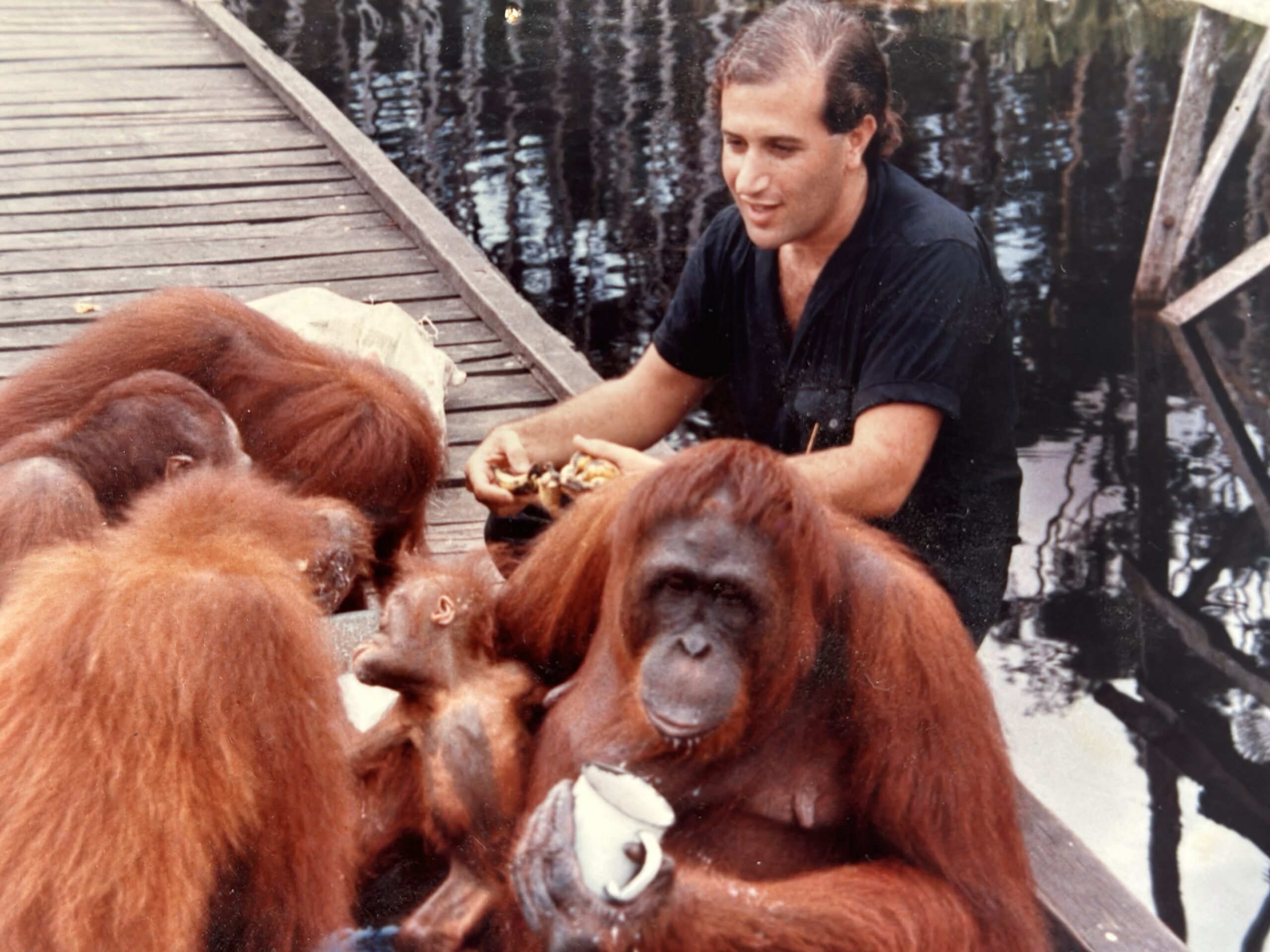

Now remember I mentioned how much I loved wildlife? I had signed up to volunteer with an organization called Earthwatch to travel to Indonesia, actually Kalimantan, also called Borneo, to assist one of the three women Louis Leakey had chosen to study the great apes. Jane Goodall, chimpanzees. Diane Fosse, gorillas. And Biruti Galdikas, who chose orangutans. As December approached we figured nothing would happen so close to the holidays, so I went off to Borneo.

Literally the day after I left my partner Lawrence Konner got a call from Michael saying everything was in place and it was imperative to start rewrites immediately. Lawrence tried to explain that I was in Borneo for three weeks, up a river in the rain forest without phone service. Michael was not amused.

So, while I was trudging through deep peat swamps following arboreal giant red apes, pulling dry ground leeches off my legs, Michael went back and asked Diane Thomas, the writer of Romancing the Stone whose deal they could not make to write the sequel, to do some work on it. It turned out Kathleen Turner was displeased with the set of the film. Just as an aside, we decided to enter the film with the heroic couple already bickering over Jack’s languid ways (‘Jack’ was Michael’s character). But Diane was tragically killed in a car accident after writing new dialogue. This was when Michael asked Isaacs and Levine to insert his work and do a few other things in the early scenes.

Remember the seagulls. For WGA credit committees, a writer who replaces another writer has to change 50% of the writing if it’s an original script or at least 30% on an adapted screenplay. Isaacs and Levine shouted, ‘Mine! Mine! Mine!’ as some writers will and tried to change things they were supposed to leave alone — including character names which is one of most lowbrow ways writers think they can fool a credit committee.

When I returned from Borneo — having had a life-altering experience that inspired me to remain involved with helping the Great Apes to this day — I learned what had transpired. My poor writing partner had taken the blows. I was humiliated. But Michael, who is basically a kind, insightful and delightfully cheeky guy, had us come up to his estate in Santa Barbara and, after making me squirm, got us back to the script. He kept what Diane Thomas had written in some of the early scenes — but every single word Isaacs and Levine had padded the script with was excised. We completed the rewrite, and we were flown to the set in Morocco to do a production polish and table reads. That’s a whole other story. Kathleen Turner, who was flying with her husband, remained openly hostile to us. She would not speak or even look at us even though we were all alone on the upstairs lounge of the 747 on the 7-hour flight to Morocco! Only the wonderful Avner Eisenberg who played ‘The Jewel’ was congenial. A more mature actor might have used the flight to tell us what she wanted from the script. Not a word. In fact, when we landed in Morocco, we had to transfer to small planes to get to the city of Fez where the crew was based. Katheleen and her husband disappeared without telling us what they said! We finally found some airport officials who just got us to the 6-seater plane in time. The flight over the Atlas Mountains was extremely turbulent. And after we settled in Fez the turbulence continued. The shame is I had already figured out how to give Katheleen what she was looking for with her character. I wrote her I think a wonderful speech about being a ‘storyteller’ at heart and that however many adventures she went on, it is always the story that endures. Never to be.

The movie was shot. We, of course, received full credit since except for a few lines every scene was written by us. There was an extravagant premiere, and a wonderful party at Michael’s home in Santa Barbara, Michael sent a very lovely bouquet to my mother on her 70th birthday and also a leather bound copy of which he signed of the official shooting script.

But let’s cut to March 2024. Remember Isaacs and Levine?

The New York Times was doing a remembrance of Diane Thomas and the writer, Bob Mehr, who wanted to discuss The Jewel of the Nile, contacted — who else! — Isaacs and Levine. Mine! Mine! Mine! They told him that Kathleen had us fired after the first draft; that they actually wrote the script; and that Kathleen ‘balked’ at our story. They implied the only reason they didn’t receive credit was because the crew was winging it in Morocco. If Bob Mehr, or Isaacs and Levine for that matter, knew anything about film production, they’d know you can’t improvise a shoot with the huge action sequences we created. One of my favorites was our ‘F-16’ gag. We put ‘Jack’ and ‘Daine’ into an F-16 jet plane to try and escape. of course, Jack can’t fly. But he manages to maneuver it like a race car to get away. There is also a wild train chase, Sufis on a posse of camels, ersatz Fascist rallies, and on and on. All of these require months of planning, props, and stunt coordinators. Doing Sit Coms their whole lives, Isaacs and Levine assumed it was like ad-libbing punch lines on a 3-camera set! The fact that a New York Times journalist who writes about films couldn’t see this problem, is shocking.

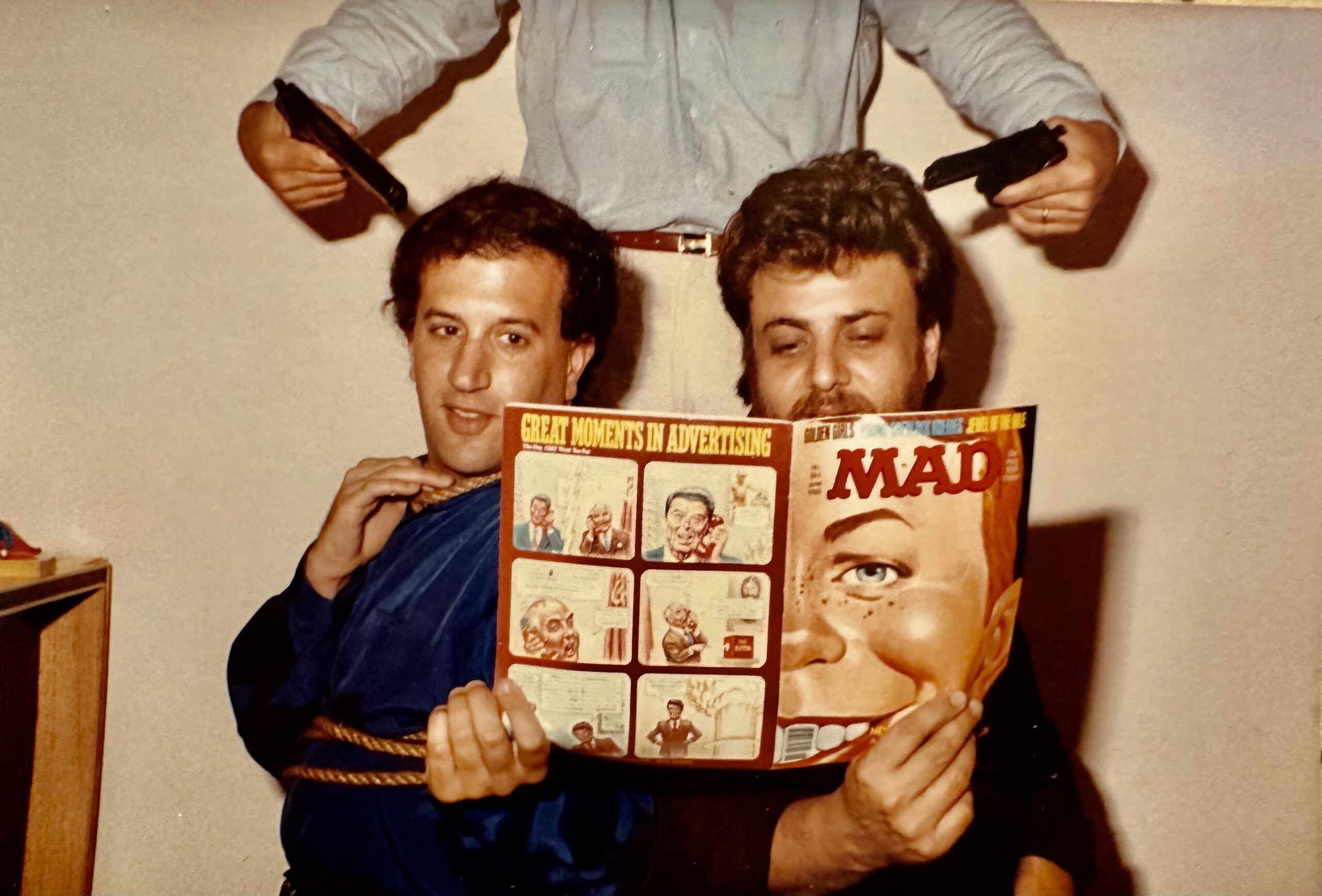

In the end, while some screenwriters may not get the credit they crave, the journey itself becomes a testament to their resilience—and perhaps their slightly less-than-sane obsession with film credit. The best way to credit — to get what’s Mine! — is to write a script into production. In the end, we also received a very special ‘credit’ — a parody in Mad Magazine by the legendary Mort Drucker. My favorite credit of all!